Materiali

ExxonMobil chief executive, Rex Tillerson, has said fears about climate change, drilling and energy dependence are overblown.

In a speech on Wednesday, Tillerson acknowledged that burning of fossil fuels is warming the planet, but said society will be able to adapt. The risks of oil and gas drilling are well understood and can be mitigated, he said. And dependence on other nations for oil is not a concern as long as access to supply is certain, he said.

In his speech and during a question-and-answer session afterwards, he addressed three major energy issues: climate change, oil and gas drilling pollution, and energy dependence.

Tillerson, in a break with predecessor Lee Raymond, acknowledged that global temperatures are rising. "Clearly there is going to be an impact," he said. But he questioned the ability of climate models to predict the magnitude of the impact. He said that people would be able to adapt to rising sea levels and changing climates that may force agricultural production to shift.

"We have spent our entire existence adapting. We'll adapt," he said. "It's an engineering problem and there will be an engineering solution."

Andrew Weaver, the chairman of climate modelling and analysis at the University of Victoria in Canada, disagreed with Tillerson's characterisation of climate modelling. Weaver said modelling can give a very good sense of the type of climate changes that are likely, and that adapting to those changes will be much more difficult and disruptive than Tillerson seems to be acknowledging.

Steve Coll, author of Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power, said he was surprised Exxon would already be talking about ways society could adapt to climate change when there is still time to try to avoid its worst effects. Also, he said, research suggests that adapting to climate change could be far more expensive than reducing emissions now. "Moving entire cities would be very expensive," he said. Legislation or regulation that would help slow emissions of global warming gases would likely lead to lower demand for oil and gasoline, and could reduce Exxon's profit.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Steve Coll: How Exxon Shaped the Climate Debate

October 23, 2012, 9:35 pm ET

Steve Coll is a staff writer at The New Yorker and author of Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power. This is the edited transcript of an interview conducted on July 24, 2012.

In some ways, it’s kind of a no-brainer that Exxon would go after climate science on a very superficial level. It’s sort of in their self-interest to keep government away from fossil fuels, right? Is that how it began?

Well, there were a lot of corporations, including oil companies, that objected to the Kyoto accords in 1997. But most of them lobbied against the treaty on economic and fairness grounds that would cost the economy of the United States too much for the benefits promised, and also that it wasn’t fair that developing societies would be left out of the bargain.

But Exxon did something that I think was fairly radical, which was that they chose to go after the science. And I think that was more the results of the personal conviction of the chief executive, Lee Raymond, than it really was an expression of their rational business needs.

After all, ExxonMobil was an oil and gas company. Gas was not problematic under climate change regulation. Oil was not as problematic as coal. They were an enormous corporation with rich profits. They could have survived Kyoto. They could have survived a price cap on carbon. They could survive on that. But they chose not only to oppose the treaty, but to attack the science.

So they could have in a sense written a check for what Kyoto called for, and instead not only went after the treaty but every scientific basis or even thinking about climate change as a threat to the world.

Lee Raymond — who had a doctoral degree in chemical engineering and who had a personal conviction that he understood the science well enough to reach a judgment about it — decided that the science was wrong.

He believed that it was a hoax, in effect, that the earth was not warming at all. … So he not only went after the treaty bargain, but funded, often in the early years surreptitiously, campaigns to attack the science that were carried out by nonscientific groups, often by free-market ideologues, … this out of an organization, ExxonMobil, that is in fact quite dependent on scientists and science. In time, perhaps we will understand what the internal reaction among scientists within ExxonMobil was to this campaigning, because there’s some evidence that within ExxonMobil, there was study going on about how global warming could affect oil discovery, for example.

So on the one hand, the chief executive was saying there is no global warming, and on the other hand, scientific departments of ExxonMobil were looking into how, if there was global warming, ExxonMobil could profit from it. …

What sort of tools were at the disposal of Exxon to really go after the science? After all, isn’t science science?

Well, money to fund campaigns raising doubts. I mean, science is science, but science is based on doubts. Science is based on arguments. Science is based on honest dissent. There is hardly a branch of science where you can’t identify a single scientist who doesn’t have an opposing view. In fact, scientists are trained to question and doubt.

In the case of climate science in the late 1990s, the consensus was still forming around how confident scientists could be about the cause, the contribution of human industrial activity to warming, what the risks over what period of time would actually turn out to be.

Here in 2012, we have a much clearer sense of what the modeling warns us about than was available in 1997. And so ExxonMobil was able to exploit genuine divisions that were still present in a global scientific community.

Those divisions were narrowing; they were closing. They would vanish within five to seven years. But ExxonMobil drove a wedge into that debate, exploited the dissent that is an aid to science and used this to create doubts in the public mind about whether the science was legitimate.

“ExxonMobil drove a wedge into that debate, exploited the dissent that is an aid to science and used this to create doubts in the public mind about whether the science was legitimate.”

After all, this is a kind of science that is very difficult for any ordinary American to evaluate on his or her [own], and we all know that weather is uncertain. We all watch the weather forecast every night and watch the weathermen who are presumably trained meteorologists and [who] get it wrong over and over and over again.

So here comes a campaign suggesting that this very consequential weather forecast might turn out to be wrong. Well, there’s an intuitive way in which Americans are going to take that up, especially if it’s propounded in a clever way that emphasizes what’s uncertain and what’s unknown. …

And the moment they concede that uncertainty, who’s poised to take advantage of that?

Well, ExxonMobil and the rest of the fossil fuel industry can rightfully say, “Scientists themselves are uncertain about exactly how warming will unfold.” And then you can go further, as Lee Raymond did. …

Lee Raymond, the chief executive of ExxonMobil, said at a shareholders’ meeting around 2000, “I’m not convinced that the earth is warming at all.” In fact, he said publicly that he feared that an ice age was more likely than an age of catastrophic warming.

And called it a hoax?

I’m not sure that he used the word “hoax,” but he in effect said, “I don’t believe there is convincing evidence that the earth’s temperature is going up in a meaningful trend.” At that point, by the late 1990s, there was really no doubt in the scientific community that the earth was warming.

The only remaining controversy at that time in the late 1990s was how confident scientists could be that industrial activity was an important or the most important forcing mechanism in the warming that everyone agreed was occurring. But Lee Raymond didn’t even concede that the warming was occurring. …

Describe this sort of freedom-fighter group that Exxon funded that would basically take on not only the science, but also the politics of what climate science was driving.

The most radical of these groups were free-market advocates, some of them medium-sized by Washington standards, some of them quite small and almost purpose-built to campaign against climate science.

They were often led by non-scientists, economists or public policy advocates. And they were specialists in communicating to members of Congress, to opinion makers, to Republican activists and to the public about matters of public policy.

So they essentially developed a campaign, a kind of multiphase, self-conscious communications campaign to try to put across the arguments that they felt most strongly about. This included tax on the Kyoto accords treaty on economic-unfairness grounds. But they also included campaigning against the science itself.

And how much money are we talking about? What kind of resources did Exxon and others bring to the table?

Well, multimillions of dollars were spent on this. And the records suggest that much of the oil industry’s contribution to this funding was routed through the American Petroleum Institute, which is where the oil companies individually often do the lobbying that’s most likely to be controversial, because then they have the shield of an industrywide group.

Within API, ExxonMobil is by far the biggest player. Dues and in effect voting power are allocated on the basis of corporate size. And so Exxon, as the largest corporation, was the big fish. And also Lee Raymond, the chairman and chief executive, was the one who really drove this agenda. We have minutes and records of the American Petroleum Institute from this period that made clear that Exxon really took over this campaign and drove the funding and the strategy in the years after Kyoto.

In addition, there were other participants from the coal industry and from other ideological and industry groups that supported this work. But the oil industry-led work involved spending millions of dollars per year over a number of years following the enactment of the Kyoto accords, in particular in 1997.

… Did Exxon rely on scientists to make their argument in anything?

Sure. They, like the campaigners, built petitions of various kinds of scientists who agreed with this critique. Now, there was a particular petition that was circulated at this time that turned out to be highly flawed and contained the names of pop singers and other phony signatures that really didn’t have any scientific background.

But there were a handful of credited scientists at mainstream universities and other organizations, some of them qualified in the relevant fields, who expressed doubts about the conventional wisdom at that time in global warming and climate science.

And although they were a very small minority of the total number of scientists working in this area, they were prepared to be forceful in their dissent. And science, of course, has often thrived on the lonely dissenter. So ExxonMobil rallied to these individuals who were, in its mind, bravely defying the United Nations and the conventional wisdom of the liberal environmental elites and called attention and provided funding to these dissidents, and then used their messages, their scientific credentials and their arguments to campaign before the public to raise questions about the credibility of what was becoming more and more a consensus science.

Aside from this handful of dissenters, though, was the argument driven by ExxonMobil made mostly by nonscientists?

A lot of these groups were run by economists, litigators, lawyers and public policy specialists, people who specialized in getting a message out, not people who were scientists. This was a Washington campaign. This was about influencing the media. This was about creating a false controversy really in proportion to the dissent versus the majority.

The effect of the campaign was to persuade many people in the media that this was an even-sided debate; that there were people who thought global warming was going on and an equal number roughly who thought it wasn’t, and that, therefore, by the conventions of impartial journalism, every story that covered legislation or other controversies around global warming should equally quote from both sides of the debate. That was a goal, an explicit goal that was written down as part of this campaign.

Let’s create doubt; let’s create a sense of a balanced debate and make sure that these lines of skepticism and dissent become routinely a part of public discussion about climate science. And, in fact, they succeeded at that.

This group may not have been scientists, but they were really good at this sort of thing.

Well, some of them actually came out of campaigning on behalf of the tobacco industry in the 1960s, which was a campaign that over a period of 10 or 15 years managed to prolong the period in which the American public believed that there might not be much danger in smoking.

Even though the tobacco companies internally knew as long ago as the 1950s that smoking was quite dangerous to human health, it really wasn’t until the 1970s or later that the evidence that this was no longer a debatable subject became part of a political consensus in the United States.

And that delay period before lawsuits and other factors caused the tobacco industry to be held accountable for the misinformation that it had communicated to the smoking public, that was the product of a similar communications campaign. …

So replace human body with climate and carcinogen with carbon, and you pretty much have the tobacco industry debate upgraded for climate science in the 21st century?

These are complex systems. How can we be certain what factors are going on? Even observing change over time is a very complicated endeavor. And listen to the scientists themselves; they’ll tell you they don’t know the answer to every question.

Since there’s so much uncertainty, therefore, we should be very cautious about undertaking costly restrictions or regulations inhibiting human freedom and all of the rest of the arguments that go along with that. Yes, there is a similarity.

When did this success in terms of messaging become a PR problem on some level for Exxon?

Well, environmental groups, scientists and later members of Congress became aware of this campaigning, because it was right out in the open. And some of the groups that were carrying it out looked by their nature to be underqualified to be entering into a politically important debate about science and public policy.

So investigations began. Greenpeace conducted some of them; Union of Concerned Scientists conducted some of them. Other important environmental groups in Washington started looking underneath the hood. …

And gradually, these mostly nonprofit groups and some journalists were able to describe by 2003, 2004, pretty thoroughly before the public, that these groups were certainly well funded by the oil industry, if not in some respect an instrument of oil industry lobbying.

Of course, these groups all said: “Hey, we believe this on our own. We are independent libertarians or free-market groups. We will have these convictions whether ExxonMobil was providing us with hundreds of thousands of dollars, and we are not.”

Maybe that’s so. But in any event, they were amplified in their messaging by the amount of resources they could tap from industry during this time.

At ExxonMobil shareholder meetings, some of these activists and dissenters started turning up to protest ExxonMobil’s funding of such groups. And initially, there was just a kind of public argument with Lee Raymond defiantly on the stage putting up his slides of scientists that agreed with him and telling shareholders: “I don’t even think the earth is warning at all. You people are wrong.”

But the more these investigations went on, the more the dissent about ExxonMobil’s fairly radical decision to attack the science began to attract really mainstream dissenters among the shareholder community as well as the environmental community. And now the people turning up at ExxonMobil shareholder meetings were a little bit less predictable.

The Rockefeller family split in half. And members of the Rockefeller family — from which ExxonMobil is descended from the Rockefeller Standard Oil Trust — they turned up at the shareholder meetings to say: “We think you are tarnishing the legacy of our great-great-great-grandfather. We think a respectable American corporation of your size, the largest corporation owned by shareholders headquartered in the United States, ought to act a little more responsively about matters of public science and public safety.” …

So that kind of dissent started to attract attention. And I think it bothered the board of ExxonMobil as the years went on. I think it bothered senior management.

I think they felt that they had been a little bit exposed by Lee Raymond’s personal convictions about this beyond where their business interests lay, because really, if the Congress in the United States in 2004 had imposed a $20-a-ton price on carbon-based fuels as one response to mitigate global warming, … that price, if it had been enacted, would have affected ExxonMobil’s business prospects hardly at all. They were a very profitable, durable oil and gas company. The price on carbon would have advantaged natural gas over coal, just as it would now. Half of ExxonMobil’s oil and gas holdings around the world are natural gas, so in a sense they could even have been winners.

Yes, it would have been a little more expensive for them to sell oil and operate some of their refineries in the United States. But none of that would have damaged ExxonMobil’s business in some existential way, … which made their actions attacking the science, in my judgment, all the more radical.

… What was their perception of the liability at the end of the day?

Well, there are different kinds of liability that I think they feared. I think the most severe liability that they feared — although it never has materialized — was comparable to the liability that ultimately bankrupted many tobacco companies, which was, there was a movement in the environmental industry to litigate against ExxonMobil for funding this campaign against climate science.

The idea was that they might be held liable for essentially undermining the available information to the public and the Congress.

Perpetuating an idea that was, number one, false, and number two, undermined public health?

That’s right. And there was a movement to try to identify victims of global warming who might try to hold ExxonMobil accountable. And of course, if such litigation were permitted to go forward, then lawyers for these victims, whoever they might be — residents of an island that was destined to come underwater if the sea levels rose, for example — they would be able to access internal records of ExxonMobil, much as happened in the tobacco industry. And perhaps that would reveal that ExxonMobil, for example, had internal scientists telling them all along global warming is real even while the corporation was campaigning against the science.

So they were very concerned about those kinds of big-ticket liability lawsuits, the kind that went after the asbestos industry, the kind that went after the tobacco industry, because when those kinds of lawsuits succeed, then an industry and a corporation can be in real peril. …

ExxonMobil’s most profitable business is at the wellhead, where they discover oil, pump it out of the ground, sell it wholesale to some user inside the corporate family or outside. That kind of activity, offshore, Nigeria, in Russia, all around the world, [was] not likely to be so affected by American greenhouse gas regulation.

Where they had some expenses that they would have to [incur] was mostly in the refinery operations, these giant factorylike plants where crude oil is converted into gasoline or precursors for the chemical industry or aviation fuel or other products.

Now, those are polluting, hot-running, very complicated industry plants that would be subject to these either prices in a cap-and-trade system or regulation if the EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] declared them to be polluters.

But in truth, ExxonMobil’s profits, circa $40 billion these days, are durable against any such regulation or carbon pricing. First of all, these refining operations represent a small percentage of their profit making. In fact, they are the most difficult aspect of their business, the least profitable.

Secondly, they are, by and large, wholesalers. So even if they have to incur incremental costs in order to comply with these regulations, they’ll be able to pass those prices down to the ultimate consumer. It’s not clear that the rates of profitability are jeopardized at all.

So in a business sense, not only was it to some extent irrational to act so radically on the subject of climate science, but, you know, also as Lee Raymond’s successor, as Chief Executive Rex Tillerson later acknowledged, it actually hurt ExxonMobil, because what they want is price stability. They want a world that is consistent across 20 or 30 or 40 years, because their whole business model is based on very expensive long-term investments. What messes up their business model is volatility, things that are unexpected. And one of the sources of volatility in the future is, they don’t know how climate is going to be regulated.

So there were many other oil companies that thought it would be smarter to get ahead of this problem, create support for a stable system, even if it was a little more expensive for them, that would at least create a degree of certainty over 20 or 30 years about what kind of environment they were operating in. But ExxonMobil went a different way.

So at what point did they get out?

At the end of 2005, Lee Raymond retired, and he was succeeded by a man named Rex Tillerson, who continues to run ExxonMobil today as chairman and chief executive. Now, Tillerson has acknowledged that when he came in he wanted to change ExxonMobil’s communications strategy around climate and other controversial issues. He has acknowledged that he thought the company had a problem.

Now, when he started to change, he did two things. First, they reviewed some of these free-market groups that they had been funding, and they cut funding to the most radical among them, especially the smaller, sort of purpose-built groups that were just concentrating on attacking climate science. And then they tried to recalibrate, reposition ExxonMobil’s thinking about global warming.

Now, their lawyers, I think, were very cautious about this and didn’t want ExxonMobil to admit liability, admit that it had been doing anything wrong before. So at first, their communication strategy was: “We were never wrong; we were only misunderstood. So let us tell you what it was we always meant to say.” And in the course of that somewhat convoluted new communications campaign, they started to say: “The risks of global warming are a serious matter. We’re seized of those risks and concerns, and we want to engage in a debate about those risks.” …

Then in 2009, they went further. At that time, the Obama administration had just taken office. Congress was preparing to consider and possibly enact climate change legislation, the so-called cap-and-trade bill, which would have created a marketplace and pollution credits and in effect raised a price on carbon-based fuel through a market mechanism.

ExxonMobil saw that legislation coming. They saw that the Democrats were in charge of both houses of Congress, they saw this new Democratic president with a great deal of electoral momentum behind him, and they thought, well, we can either stay out of this and get run over by it possibly, or we can come forward and start to join the debate.

So Rex Tillerson flew to Washington in January 2009, and he made an appearance at a think tank called the Woodrow Wilson Center, and he announced that ExxonMobil for the first time supported a carbon tax. It did not support the cap-and-trade mechanism, which it believed was too bureaucratic and unwieldy. But, it said, in principle, we do support the goal of that cap and trade, which is a $20-a-ton, roughly, price on carbon-based fuels. We think it ought to just be imposed straight across the board. But we’re in the game.

Now, some people greeted this announcement with skepticism, thinking that ExxonMobil had just found a new way to oppose the main bill that was on the floor. And in truth that’s what they did. They went out, and they lobbied against cap and trade, which ultimately died for a variety of complicated reasons, mostly having to do with the recession.

But for the first time, the chairman and chief executive of the largest oil company in the United States said forthrightly that the risks of global warming were significant enough to warrant a price on carbon in order to incent[ivize] movement away from fossil fuels. So that’s at least a change from the Lee Raymond era. …

So Exxon walked away. But was damage done?

The public’s doubts about climate science suggests that the legacy of these investments and their campaign after the Kyoto accords is still with us. I can’t think of an area of science that is relevant to public policy where the gap between what most people believe and what 97 percent of qualified scientists — however you want to define that phrase — believe is as wide as in the case of climate science.

“I can’t think of an area of science that is relevant to public policy where the gap between what most people believe and what 97 percent of qualified scientists … believe is as wide as in the case of climate science.”

The truth is there really is no debate within climate science about some really important fundamentals: a, the earth is warming at a dangerous pace; b, industrial activity is a forcing mechanism and that unless it is reduced, the pace of warming will continue; and c, while we can’t be exactly certain which in a range of outcomes we will get, even in the best case, unless we reduce the amount of greenhouse gases that are being forced into the atmosphere, global temperatures will rise to a dangerous degree.

By dangerous, I mean they will affect global agriculture. They will raise sea levels to a point where they will threaten coastal inhabitants in settlements all around the world. And they may create even more extreme changes in climate that would affect human settlements from Europe to sub-Saharan Africa. …

The impact of these groups, when you looked into this, did it surprise you?

It surprised me that their ideas are still so alive in the public mind. I think there may be an explanation, which is that if you look at American history since the Second World War and since the birth of the environmental movement, really in the 1950s and 1960s, Americans have proved over and over again that they’re willing to tax themselves to protect living generations from pollution.

So if air pollution threatens the health of your son or daughter, if water pollution threatens the health or increases the likelihood that your granddaughter will contract cancer or some other disease in her lifetime, then you are willing to act.

Even if you are a free-market ideologist, you are willing to say, “This is what government is for, to protect us from acute threats to living generations.”

The problem with climate change is that until recently, I think to many Americans, it has seemed like a threat not to living generations but to future generations. And with that uncertainty, and with the economic climate that we are in, Americans have been unwilling to impose a tax on themselves in order to protect generations as yet unborn.

Now, elsewhere in the world, in the industrialized world, we have seen this equation change when extreme weather has caused living generations to say to themselves: “You know what? This may actually be more like air pollution or water pollution. This may be a threat to living generations. We may be looking at droughts or extreme weather events that could affect the quality of life of my grandchildren who are just 5 years old now.”

In Australia, a country that has politics as resistant to climate regulation as any of the United States, the country just enacted a price on carbon. Why? They just endured the worst drought in recorded Australian history. …

Of course, no scientist can tell you that any particular weather event is directly a result of global warming. But what they can observe is that their prediction has always been that as this process unfolds, extreme weather events will become more frequent; there will be more volatility; and some of the effects, such as the ones we’ve seen, will include drought and extreme temperatures.

So it may be that over the next 10 or 15 years, Americans will reconsider the ideas that were propounded by these campaigners funded by the oil industry in the 1990s, which is to say that there’s a lot of doubt about all of the tenets of this science, and follow a different kind of intuition, which is that this is here with us now.

Do you think down deep inside Exxon somewhere, there’s a fear that a corn farmer in the Midwest looking at a completely brown field today, because of this campaign against the science launched by Exxon, that that farmer will become a plaintiff in the future in some lawsuit related to climate change and global warming?

If I were an ExxonMobil lawyer, I’d be worried about just that scenario. I absolutely would.

ExxonMobil is a corporation with many scientists employed in the United States within its geology departments, within its exploration and engineering departments.

Scientists are all ornery, independent people on the whole, and they have been trained to question consensus thinking, question their superiors, question everything around them. It would be surprising if ExxonMobil had carried out such an anti-science campaign over eight to 10 years and had never had one of its own scientists write a memo inside the corporation that said: “What are you doing? I have a contrary view,” or, “My reading of the evidence is different than what you are funding groups to say,” or, “I’m concerned that we are creating unnecessary liability for ExxonMobil by spreading false ideas.”

Those documents, if exposed by a plaintiff in a lawsuit, whether they were a corn farmer who suffered drought or the inhabitant of some island that started to sink under rising seas, could change the liability that ExxonMobil and other corporations may ultimately face.

Now, remember the instance of the tobacco industry. First of all, those documents were written inside those companies, dissenting documents, in the ’50s and ’60s. It wasn’t until the ’90s that they came out through lawsuits. The wheels of justice are slow.

And in fairness to ExxonMobil, whatever the debate inside the scientists within that corporation, we’re not talking about the same thing as smokers. We’re not talking about what tobacco industry scientists knew, which is that living human beings smoking cigarettes were more likely to die as a result of the withholding of this information. I mean, even in the worst case, the effects of climate change, our collective effects, they’re global effects. They’re going to unfold over a period of decades, and they’re going to unfold in an uncertain pattern. …

This is a very moralistic company. It’s a company that has inherited a very strict ethical regime from the Rockefeller days. Former managers told me as recently as the 1970s, it wasn’t unusual to go to a meeting at Exxon and sit down and pray together before the meeting began. The current chief executive is a self-described evangelical Christian, and there’s quite a lot of moralism in the way the corporation speaks to its constituents and to its employees.

So how do you square that with a campaign that I think will be judged by history as a radical and, in some important respects, dishonest campaign? I can only assume that the authors of that campaign at the corporation say to themselves: “Oh, we didn’t know. There was some uncertainty. And if we’re later proved that our doubts were misplaced, well, they were doubts honestly held at the time, because nobody knew 100 percent of where this science was going.” …

What kinds of groups are they funding now that might have anything to do with this?

… I think they have pulled most of the direct funding for the groups that were campaigning against science in the years after Kyoto, but they’ve remained part of an industry coalition that is focused on delaying any price on carbon and maintaining political resistance to efforts at the Environmental Protection Agency, efforts in the Congress or elsewhere to take any approach that would curtail industrial activity on grounds of climate regulation.

What’s the synergy, if any, between Exxon and the Heartland Institute?

The Heartland Institute was one of the nonprofits that received funding from ExxonMobil during the years that it was campaigning to challenge climate science after the Kyoto accords were enacted.

The Heartland Institute’s tax returns describe the revenue they received from ExxonMobil, and, curiously, they list on one of their returns an ExxonMobil executive who was a lobbyist in ExxonMobil’s Washington office, a gentleman who had come from ExxonMobil’s chemical company, and he’s listed at the Heartland Institute as a government adviser, suggesting that the relationship between Heartland and ExxonMobil went beyond just that of a donor and a recipient organization but that there was some kind of active consulting or advising that was also a part of the partnership. …

As I understand that, they’d say that they don’t receive direct funding from ExxonMobil anymore. And this is one of the institutions that was I think on the list that ExxonMobil made after 2006 where they decided to reduce their funding. …

What do we know about this specific review done on these advocacy groups that caused Exxon to decide to pull a plug on some of its operations?

As this transition in the chief executive’s office took place, the new chief executive ordered a group to study the investments that ExxonMobil had been making to review the communications that ExxonMobil had been putting out and to start to propose alternatives. And in the course of that review, a decision was made to end the funding for the most radical groups and also to publicize the fact that ExxonMobil had ended that funding because they wanted it to be understood that they were making a change.

And certain groups didn’t pass muster.

The smaller groups and the ones that had attracted the most controversy and attention from investigators. And the ones that were not on the main led by scientists seemed to be ideological and really more geared toward public relations and communications strategy than toward public policy research or scientific research.

But the $26 million investment that Exxon made up to that point really created the infrastructure for what today is a very successful battle being waged against candidates in the 2012 election.

Yeah, there’s no question that that movement continues and that it continues to publish, and it continues to pursue many of the same arguments that were developed in that period after the late 1990s. …

______________________________________________________________________________________

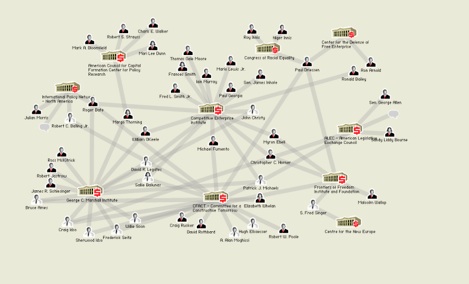

Exxon funding of climate skeptics/ source: Greenpeace

see the complete list in the website in the link above.

lunedì 28 gennaio 2013

Exxon: the climate skeptics market